“What’s important about money to you?” The response to this critical question invites a higher level exploration beyond those tangible possessions which can provide transitory satisfaction. Study after study shows that lasting happiness and fulfillment can more often be attained by understanding our deeper emotions, e.g. our values and priorities. Yet as important as it is, this critical question all too often goes unasked and even less often, gets answered.

What frequently gets lost is the role money plays as a means to an end rather than an end in and of itself. The things we really care about, what gives us a sense of fulfillment, are the real payoffs that money can help us secure. These define our core values, the things that motivate us and give our lives meaning. Articulating values communicate those things important to us that can help us gain more happiness ourselves, bring spouses and families closer, and can serve as important role models for our heirs. It can also lay the groundwork for a family mission statement that can help establish a family’s identity.

If we think of articulating our values as a process, then defining what is a value could serve as a good starting point. Values are the qualities and principals that are most intrinsically dear and desirable to us. As such, they are given particular significance by the specific words we may use to describe them. They are those life intangibles that give us a deeper, more sustainable emotional “high” beyond fleeting pleasures of the moment. The attainment of our values is what gives our lives true, lasting meaning and contentment as life’s emotional payoff.

When we talk about family values, we refer to “… a traditional set of social standards defined by the family and a history of customs that provide the emotional and physical basis for raising a family. Our social values are often times reinforced by our spiritual or religious beliefs and traditions.” In short, family values consist of those important ideas that are passed down from generation to generation that help us define how we want to live our family lives.

In his book Values-Based Financial Planning: The Art of Creating an Inspiring Financial Strategy, Bill Bachrach suggests a Five Step Process to starting a values conversation between partners:

- “Your partner asks you a simple question: ‘What’s important about money to you?’

- Your job is easy; just answer truthfully and as honestly from the heart as you can. Take as much time as you need, and give the first answer that comes to mind without overanalyzing.

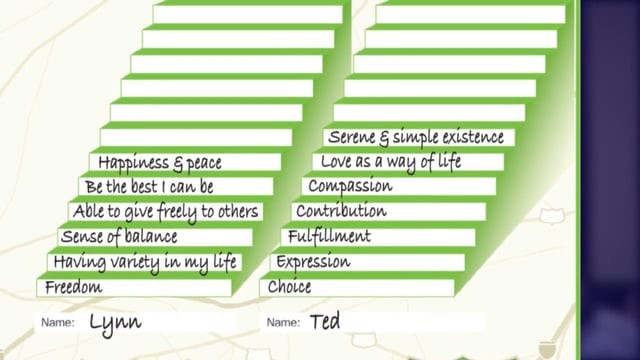

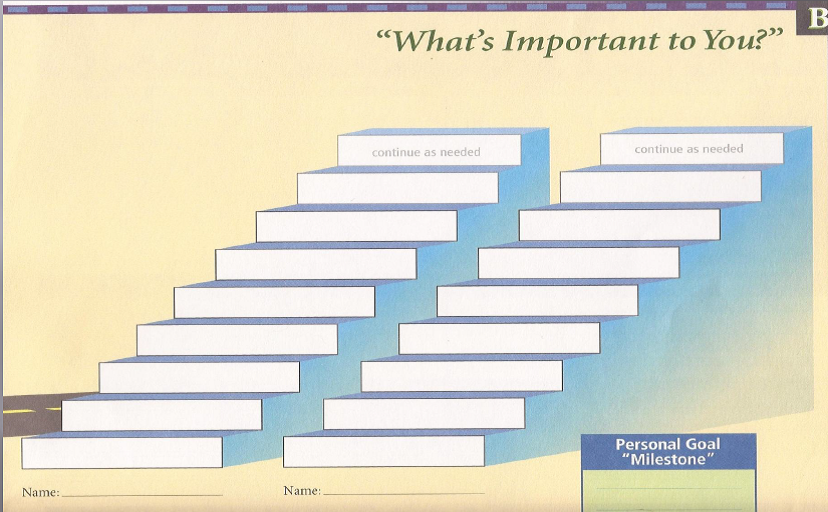

- Your partner records your answer toward the bottom of a sheet of paper (or use the worksheet provided in Bachrach’s book, an example of which appears in Appendix 1) that serves as a Values Hierarchy or “Staircase”.

- Then your partner builds on your answer by asking another question, substituting your value for the word money: “What’s important about [your last answer] to you?

- Again you respond with your first thought, your partner records it, and then he or she asks you the question again “What’s important about [the value you just said] to you? And so on up the staircase.”

Money, like values, has meaning that differs from person to person. For some it can offer security. For others, freedom and independence, and likely something very different to others. Having the patience to “drill down” with this process can help us access our deepest levels of emotions. Responses such as independence, accomplishment, making a difference, providing for family, inner peace, spiritual attainment, and self-worth can serve as statements of value that provide powerful inspiration. While your core values may be completely different from these, it is important to keep in mind that there are no wrong answers; your answer is always the right one for you.

The benefit this exercise offers is often found in the “drill down” phase. As Abraham Maslow postulated in his “Hierarchy of Needs”, the starting level relates to essential biological and safety needs such as food, water, shelter, protection from danger, disease, and fear. Once those are satisfied, Maslow believed that attention could then focus on higher psychological, social and emotional needs such as love, belonging, esteem from self and others, knowledge, and aesthetics such as beauty. As those are fulfilled, the highest “self-actualization” needs such as realizing one’s potential and enjoying “peak” experiences, become more achievable.

With Maslow’s Hierarchy as context, we often find three similar levels of response to the “What’s important about money” conversation:

Level 1 – Lower Self: Many will start with the more obvious answers about the “lower self” as Bachrach calls it. Responses that include tangible goods are simpler, less threatening and easier to access. They often relate to more immediate, physical benefits and obtaining tangibles.

Level 2 – Thoughtful Self: Pushing a little further may generate more thoughtful responses that pertain more to others than to self, such as making a difference, providing for family, social consciousness, or having a positive impact on community. The tone is less about immediate gratification with tangibles and more about doing for or giving to others.

Level 3: Higher Self: At this level responses can take on a more expansive tone and focus on areas with greater potential internal/emotional payoffs. These can be aspirations like becoming the best person I can be, inner peace and contentment, spiritual fulfillment, enlightenment, etc. This is considered the level of pure emotion where there is a noticeable lack of tangibles and emphasis on real life purpose.

Sample Values Ladder

Keep in mind that most of us do not speak of our values very often. So responses can bounce around from one level to the next as part of this spontaneous process. People can also become anxious or even a little defensive as they drill deeper. This is perfectly natural. Bachrach suggests some important guidelines to help make this values conversation as effective as possible:

- Choose a Good Partner: Someone who is genuinely interested in your responses and who can help support your completing the exercise. Two key guidelines that to consider:

- Stick to the inquiry format of “What’s important about __________ to you?”

- Don’t interject or offer suggestions. Especially for spouses who may be tempted to even complete each other’s sentences, this may be particularly challenging but try to refrain.

- Stay Focused: As we drill down, people may become more anxious and may be tempted to stray by perhaps discussing their responses before the exercise is completed. Focus is tough enough, so for best results try to stay on task.

- Be Spontaneous: The first response is usually the most genuine and it may take time. Keep in mind that the exercise is not timed and this subject matter is not often top of mind. Patience is key. In fact, clients have spoken of instances when answers were hard to come by. By moving at a more leisurely pace they felt more satisfied with the experience.

- Stick to the Format: Best results occur when clients stay dedicated to the format. Strictly staying with the questioning format of “What’s important about money to you?, then following up by substituting the last value given with “What’s important about _______ to you?” is your best assurance of gaining a sincere, meaningful result. Try not to vary the words or the order they are said.

- Even seemingly minor changes such as “Why is money important?”, “What does money mean to you?” will likely not get the same meaningful results.

- The farther you delve into this, the more clarity you will get about your financial motivations. The end result can be a more powerfully inspired experience that can make a significant difference in your life.

- Fixing a “Stuck”: Participants may find they encounter a “block” as they move toward deeper Level 3. When this occurs, it may be helpful to picture yourself already in the position of having achieved that particular value and ask “Once I know that I have _______, what is important about having attained this that is resonating with me?” Some also find it helpful to step back, take a break, then revisit the exercise again from where you left off.

- Knowing When You’re Done: It is critical to not try to “leapfrog” ahead or force the highest value, as that could produce less than true results. The process itself, while taking some effort and introspection, contributes much to the crescendo of values at the end in revealing how each relates to the final output. Think of this as an unfolding of what matters to you, in a sense a story of you in the making. As participants near the end, they typically find their values start sounding redundant or repetitive. As that occurs, the interviewer may rephrase the questions to be “Is there anything more important to you than ___________ (being the most recently stated value).”

Values are the less obvious, often intangible reasons that motivate us. They are the emotional payoffs that guide our choices and actions. Articulating them can not only help us gain a better understanding of ourselves; discussing them can bring partners and families closer as well. They provide a framework around which we can create more meaningful financial goals. Perhaps more importantly, sharing our values can provide effective modeling and meaningful inspiration as they are handed down to our heirs.

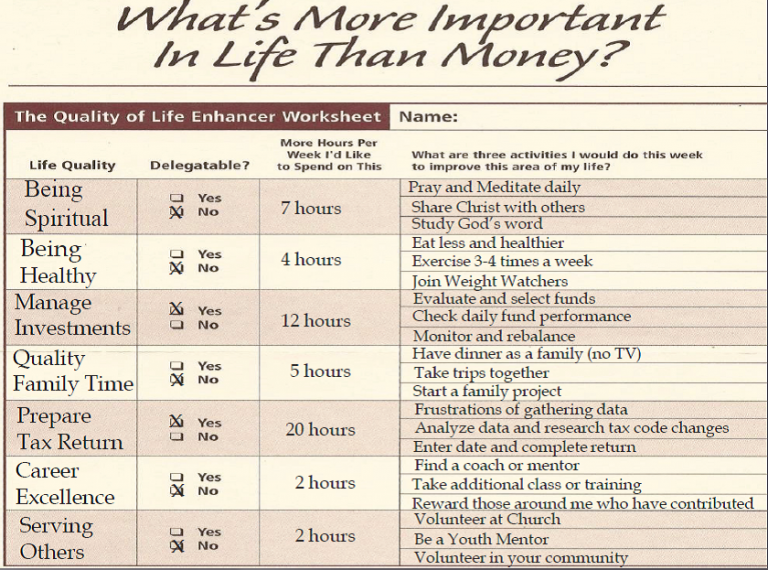

Living your values is often even more of a challenge than defining them, as it takes concerted effort, discipline and commitment. Bachrach’s “Value Ladder” (see Appendix 1) offers a convenient format for exploring your values. “Life Enhancer Worksheet” (see Appendix 2) provides a valuable structure to implement changes to help assure your lifestyle is consistent with what is most important so you can enjoy a “Life Well Lived.”

Appendix 1

Sample Values Ladder Template

Appendix 2

Sample Life Enhancer Worksheet

This information is not considered a recommendation to buy or sell any investment or insurance and is being provided for information purposes only and is not a complete description, nor is it a recommendation. We strongly recommend an advanced tax and estate planning expert be contacted for further information since Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network LLC (WFAFN) does not provide tax or legal advice. Any opinions are those of Mitchell Kauffman and not necessarily those of WFAFN. The information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network does not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. Prior to making a financial decision, please consult with your financial advisor about your individual situation. Investment products and services are offered through Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network LLC (WFAFN)/Member SIPC. Kauffman Wealth Management is a separate entity from WFAFN.

Written By

Mitchell E. Kauffman, Managing Director

Certified Financial Planner™

Mitchell Kauffman provides wealth management services to corporate executives, business owners, professionals, independent women, and the affluent. He is one of only five financial advisors from across the U.S. named the industry’s most qualified Financial Advisor through Research magazine’s Hall of Fame in 2010.

Inductees into the Advisor Hall of Fame have passed a rigorous screening, served a minimum of 15 years in the industry, acquired substantial assets under management, demonstrate superior client service, and have earned recognition from their peers and the broader community.

Kauffman’s articles have appeared in national publications, and he is often quoted in the media. He is an Instructor of Financial Planning and Investment Management at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

For more information, visit www.kwmwealthadvisory.com or call (866) 467-8981. Investment products and services are offered through Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network LLC (WFAFN), Member SIPC. KWM Wealth Advisory is a separate entity from WFAFN.

[ii] Defining Your Family’s Values by Susie Duffy, M.F.T., Parent IQ

[iii] Values-Based Financial Planning: The Art of Creating an Inspiring Financial Strategy, by Bill Bachrach, Aim High Publishing 2000, Pg. 5-6